Reflective Practice and Writing

This page contains helpful resources related to:

John Dewey, an educational philosopher, defined reflective thought as the “active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends” (Dewey, 1933, p. 9). He argued that reflection “…enables us to direct our actions with foresight…It enables us to know what we are about when we act” (p. 17).

Such deliberative thought and intention in our practice is critical to our success as educators. Stephen Brookfield argues in his book Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (1995) that engaging in reflection helps us to:

- Take informed actions – “Informed actions are those that can be explained and justified to ourselves and others” (p.22).

- Develop a rationale for practice – “A critical rationale grounds our most difficult decisions in core beliefs, values and assumptions. … It provides a foundational reference point – a set of continually tested beliefs that we can consult as a guide to how we should act in unpredictable situations” (p. 23).

- Be emotionally grounded – It helps to balance the ebb and flow of teaching successes and inevitable failures, which allows us to more effectively respond to challenges we encounter.

- Enliven our classrooms – “A teacher who models critical inquiry into her own practice is one of the most powerful catalysts for critical thinking in her own students” (p. 25).

There are several models of reflective practice that can help to guide our reflections on teaching. Pick a model that works for you and use it to help guide and direct your reflection and writing about your instructional practices.

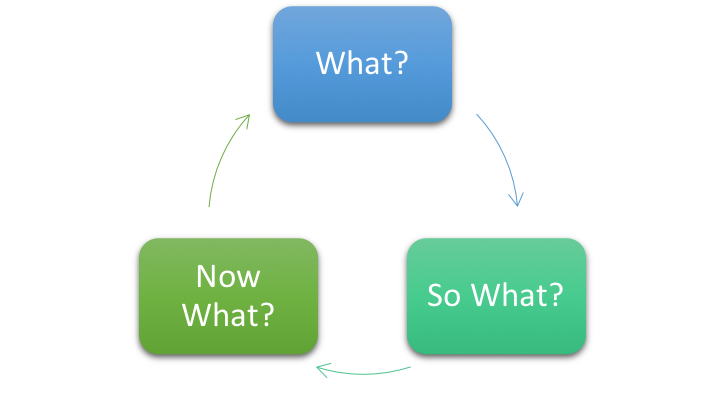

Among the simplest models proposed involves asking (Borton, 1970):

- What? – describe the experience (what happened?)

- So What? – reflect on the experience (what have you learned?)

- Now What? – consider how what you learned will impact future practices (how will I use what I learned?)

Figure 1. Borton reflection model

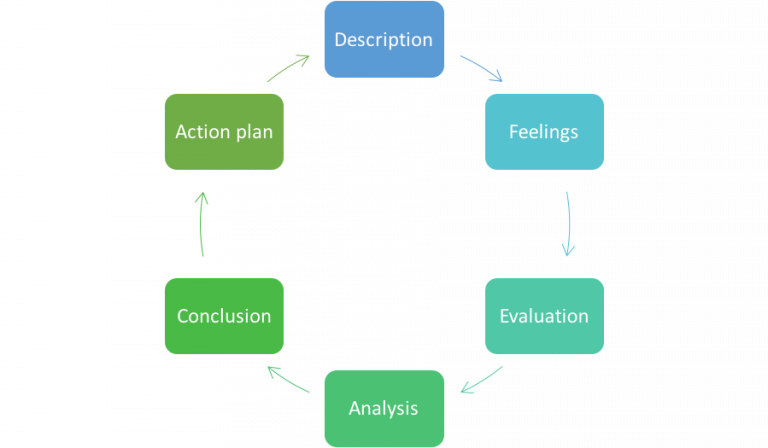

Gibbs (1998) proposed a more complex model that can help you think through all aspects of an experience.

- Description – what happened during the event?

- Feelings – what were you thinking and feeling about the experience?

- Evaluation – what was good and bad about the experience?

- Analysis – what sense can you make of the situation?

- Conclusion – what else could you have done?

- Action plan – what would you do differently next time?

Figure 3. Gibbs Reflection Model

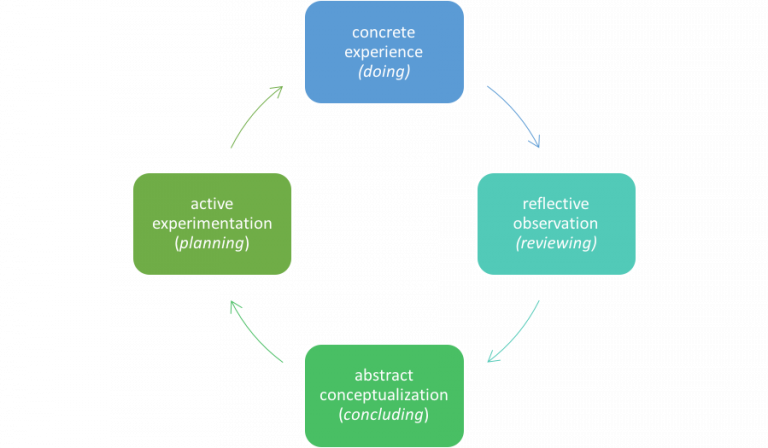

The experiential learning cycle proposed by Kolb (1984) can also be used to promote and guide reflective thought and writing. This cycle includes four stages to explain and guide how we can learn from experience.

- Concrete experience – doing or having an experience

- Reflective observation – thinking about the experience

- Abstract conceptualization – drawing conclusions and learning from the experience

- Active experimentation – planning and applying what you’ve learned

Figure 2. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle

Reflective writing involves thinking about an experience and trying to “make sense” of and learn from it. While it may involve a description of the experience, a description alone does not constitute reflective writing.

Reflective writing must also include an interpretation and analysis of the experience. The writer will consider what was important from the experience, why it occurred, what emotions it produced, how it could have gone differently, what was learned from the experience, and how that learning can be applied in the future.

Engaging in reflective writing presents an opportunity for deep and critical thought, which can result in new insights from your experiences.

The table below highlights some key characteristics of reflective writing (Sewell, 2017).

| Reflective writing is… | Reflective writing isn’t… |

|---|---|

| Written in the first person | Written in the third person |

| Analytical | Descriptive |

| Free flowing | What you think you should write |

| Subjective | Objective |

| Tool to challenge assumptions | Tool to ignore assumptions |

| Time investment | Waste of time |

Be honest and avoid censoring your thoughts

- Reflection requires honesty, which may not always be easy or comfortable for us to engage in as we consider our teaching. Give yourself the freedom and space to consider your strengths, weaknesses, successes and challenges without judgment.

- Consider engaging in a “free write” activity to begin the reflective writing process. Identify a teaching event or experience, set a timer for 5 minutes, and write continuously for that time (or until you fill a page). Write whatever comes to mind; do not censor your thoughts or edit your writing. It’s likely that some talking points or sources for further deliberation/exploration will be revealed.

Take a step back

- Sometimes it can be difficult to look objectively at our teaching, but this is precisely what needs to happen in order to fully understand and analyze an experience. If you’re struggling with this, try writing about the experience in third person language…write as if you are an outsider observing the experience and your reactions to it.

Write in response to questions

- If you’re having a difficult time getting started in your writing, draft some questions and write responses to those questions. The Gibbs model above provides some useful prompts or you may be able to construct questions more specific to the target experience.

- Some writing prompts/questions specific to the PNW Teaching Portfolio narrative topics are posted in a Padlet. You are encouraged to contribute to the Padlet by adding additional questions, ideas, sources of evidence, etc. for each narrative topic.

- Talking through your writing goals and/or experience with a colleague may also prompt the development of a writing plan or questions to which to respond.

Narrow your focus

- It will be difficult to reflect meaningfully on all aspects of all courses you taught during an academic year. While you may wish to reflect generally on overall themes in your teaching, there is also value in considering specific events/experiences more deeply. Identify meaningful experiences in relation to the teaching portfolio narrative topics and engage in the reflective thought/writing process about those specific experiences.

Consider keeping a journal for each of your classes

- After each class session, write down your general impressions of the class. What went well? What do you need to rethink for next time? Were there any unexpected outcomes?

- Having these notes will be helpful for next time you teach the class, but they may also be beneficial as you reflect on your teaching for your annual teaching portfolio.

References

Borton, T. (1970). Reach, touch, and teach: student concerns and process education. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston: D.C. Heath & Co.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as a source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs. NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sewell, C. (2017). Reflective practice workshop. University of Cambridge. Available: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/265159/MEM_ReflectivePracticeHandout_V4_20170616.pdf?sequence=1